George Levantis – U5825436

What contains 10% of the world’s fish species, 25% of all known marine species, and 85% of the world’s species of marine turtle? No, it isn’t Lake Burley Griffin.

The Great Barrier Reef (GBR) is over 300,000km2 of some of the world’s most precious biodiversity, which means thousands of km2 of protected area requires constant management. Biodiversity conservation is only as successful as its management – so with such a diverse range of challenges facing the reef, from climate-change driven habitat loss to zoning issues, is the monitoring and management we have in place effective at delivering biodiversity outcomes?

This was the question I wanted to answer in October, when I worked with a team at the department responsible for evaluating the projects funded by the “Reef Trust Partnership” (FTP). The RTP is a collaboration between the Government, Reef Trust and Great Barrier Reef Foundation, and releases annual reports on the effectiveness of projects funded by the RTP.

What makes good monitoring?

Monitoring is what underpins decision-making in management. Being accountable and certifiable is especially important in the case of the FTP which is mostly funded by tax-payer money. Good monitoring often follows the “Before After Control Impact” (BACI) principle, with monitoring that begins before an impact or change in management, after impact, and the monitoring of control sites.

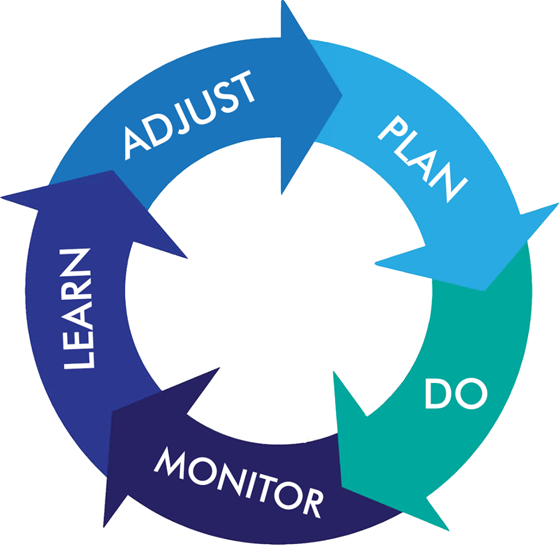

Ideally, monitoring continues to improve over time, following a pattern of planning, doing, monitoring, learning and adjusting. In the case of the GBR, good monitoring will be aware of confounding variables such as climate change impacts, seasonal changes, migrations etc. and adjust the management plan as these variables change.

Okay, monitoring is cool, so is the RTP doing its job?

Let’s look the Eastern Cape York Water Quality Improvement Plan, a project under the RTP I assessed. The projects aims to minimise water quality degradation to protect habitat. The project took an initial assessment of the important habitat features. Then, vulnerable areas were identified (Namely: Princess Charlotte Bay, a fish habitat important for green turtle foraging, and Flinders Island, a region with reefs and seagrass). Finally, risky levels of anthropogenic loads in the monitored water were determined, and corrective measurement actions pre-determined if these levels were detected.

Whilst I think this plan follows good monitoring practice, I see a potential flaw. This plan employs the use of “passive adaptive management”, as it doesn’t use a range of management actions to determine which is most effective. While this makes sense for a region that isn’t under immediate threat of degradation, sudden changes in risk can leave the management unarmed as passive adaptive management relies on long-term consistent data to make minor adjustments over time. As threats to the GBR grow over time, will relying on passive management like the Eastern Cape York Plan leave managers out of options?

References:

Brodie (2016) Brodie J. Great Barrier Reef report to UN shows the poor progress on water quality. The Conversation. 2016. https://theconversation.com/great-barrier-reef-report-to-un-shows-the-poor-progress-on-water-quality-69779 2 December 2016.

Cape York Natural Resource Management and South Cape York Catchments, 2016. Eastern Cape York Water Quality Improvement Plan. Cape York Natural Resource Management, Cooktown, Queensland, Australia.

Datta, A. et al. (2022) “Big events, little change: Extreme climatic events have no region-wide effect on Great Barrier Reef Governance,” Journal of Environmental Management, 320, p. 115809. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115809.

Dixon, K.M. et al. (2019) “Features associated with effective biodiversity monitoring and evaluation,” Biological Conservation, 238, p. 108221. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108221.

Pratchett, M.S. et al. (2011) “Contribution of climate change to degradation and loss of critical fish habitats in Australian marine and Freshwater Environments,” Marine and Freshwater Research, 62(9), p. 1062. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1071/mf10303.

Richards, Z.T. and Day, J.C. (2018) “Biodiversity of the Great Barrier Reef—how adequately is it protected?,” PeerJ, 6. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4747.

A great critique of monitoring, but they are challenging issues to address.