Marcus Dadd (u6945315)

Reptiles have long held a special place in my heart so when a fieldwork advertisement titled ‘Sex in Dragons’ popped up on my Instagram feed in the middle of Canberra’s winter I was hooked. A few months later I volunteered at Bowra Wildlife Sanctuary, just outside Cunnamulla in south-western Queensland for three weeks from the end of November to early December 2019.

Background

Despite being one of the most common reptiles in the pet trade and Australia, Central Bearded Dragons(Pogona vitticeps) are poorly studied in the wild. Offspring gender in reptiles is generally temperature-dependent or genotypic sex determination but some reptiles use both forms of sex determination.

The Study

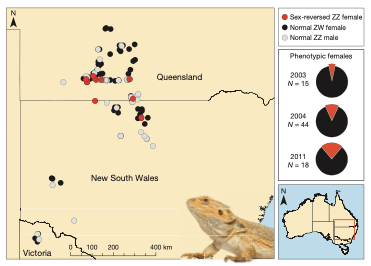

Along with five other volunteers I assisted Kristoffer Wild, a PhD candidate at the Institute for Applied Ecology with his study looking at the ‘ecological causes and consequences of sex reversal’ in Central Bearded Dragons6. Sex reversal is an evolutionary mechanism that occurs in Central Bearded Dragons at incubation temperatures between 34 and 37C. Sex reversed individuals are genetically male but phenotypically and reproductively female1. This was demonstrated in laboratory settings and first detected in wild animals in 2003.

Kris is determining sex reversal frequency and comparing the behaviour of sex reversed females to normal individuals. Other aims are to understand the spatial ecology, movement patterns, habitat selection and physiological ecology of this species.

Every dragon captured at Bowra was fitted with a jacket that holds a GPS and accelerometer so that behavioural and movement patterns can be monitored. Temperature loggers were placed across microclimates to ascertain the relationship between thermoregulatory behaviours and environmental temperatures. Metabolic rates were calculated through taking blood samples before and after injecting some water, mixed with a stable isotope.

Our Role

We used radio telemetry to track dragons for capture or to monitor their behaviour from afar with binoculars over 30 minute intervals to validate accelerometer data. With their excellent camouflage it often took us minutes to locate a lizard we’d tracked to a bush or logs. Lizards were brought back to the shearer’s quarters for body length and weight measurements, jacket repairs, downloading accelerometer data, and to take blood and DNA samples(for newly caught animals). Environmental metrics such as temperature, humidity, windspeed, shelter and vegetation were measured to understand habitat selection. Other tasks were data entry and collecting temperature loggers inside copper pipes that resemble the thermoregulatory characteristics of Bearded Dragons.

Some Challenges

Extreme conditions with temperatures reaching 45C for consecutive days made fieldwork challenging, particularly when we had to walk many kilometres, tracking dragons. These conditions contributed towards low detectability as dragons conserve energy by slowing their metabolism. Consequently we only added two new individuals to the study, despite a high survey effort with many hours walking and road cruising. High mortality is a harsh reality of studying species at the bottom of the food chain with a few dragons dying over the volunteering period.

Final Reflections

Climate change may reduce genetic variability in Central Bearded Dragon populations if sex reversed females are a significant percentage of the population as they display bolder behaviours that increase the likelihood of predation. Despite the challenges I thoroughly enjoyed my time at Bowra, contributing to an interesting and important study that has future conservation implications for Central Bearded Dragons.

Reference List

- Butler,M2017,‘UC researchers peek inside the dragon’s egg’, University of Canberra, viewed 6 September 2020, https://www.canberra.edu.au/research/institutes/iae?result_1631967_result_page=3

- Holleley, C, Meally, D, Sarre, S, Marshall Graves, J, Ezaz, T ,Matsubara, K, Azad, B, Zhang, X, & Georges, A 2015, ‘Sex reversal triggers the rapid transition from genetic to temperature-dependent sex’, Nature, vol. 523, no. 1, pp. 79-88.

- Quinn, A 2007,‘How is the gender of some reptiles determined by temperature?’,Scientific American, viewed 6 September 2020, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/experts-temperature-sex- determination-reptiles/

- Quinn, A, Georges, A, Sarre, S, Guarino, F, Ezaz, T, & Marshall Graves,J 2007,‘Temperature Sex Reversal Implies Sex Gene Dosage in a Reptile’, Science, vol. 316, no. 5823, pp. 411.

- Wild, K 2020,‘Research Interests’,Kristoffer Wild, viewed 7 September 2020, https:// www.kwildresearch.com/research.html

- Wild, K 2020, ‘Understanding the Ecological Causes and Consequences of Sex Reversal’, Kristoffer Wild, viewed 7 September 2020, https://www.kwildresearch.com/phd-research.html