U6112534 Baiyang Zhang

Word count: 503

Weed invasion leads to the deterioration of Australia’s ecological environment

Australia has a vast number of unique environments and biota due to its isolation from other continents. Therefore, it is important to maintain the stability of the ecosystem. Species invasion is one of the main reasons that lead to environmental degradation and biodiversity loss. More than 3000 invasive species have arrived in Australia. This has brought a massive disaster to the ecological environment and native species. Invasive species threaten about 82% of threatened or endangered native species. This can lead to massive declines and extinction of native species in Australia.

Weed invasion is another main aspect of species invasion. Weeds are identified as pest species because they are introduced species and growing where humans do not want to grow. In addition, weeds are operating a way that is disturbing the natural processes and is against human interest.

What negative effects do weeds bring?

Weeds have hugely affected Australia’s economy, environment, and society. Australia loses about 4 billion dollars annually in weed control measures and production.

In addition to competing for resources with native species, reducing the diversity and richness of native species, and affecting the structure and function of the natural ecosystem, weeds also reduce soil fertility, land degradation and agricultural yields for primary industry. Furthermore, weeds also affect the landscapes that we enjoyed and reduce the recreation value.

How weeds got into Australia

You must be interested in how weeds came to Australia.

Many plant species were intentionally introduced for crops, pastures, gardens and horticulture after Europeans began to colonize Australia. Some other plant species were transduced accidentally and spread rapidly. Weeds have caused substantial changes to the natural environment in Australia.

How to control the weeds

There are four levels of management of pest species, which are:

- Prevention: Species absent.

- Eradication: small number of localised populations.

- Containment: Rapid increase in distribution and abundance of many populations

- Asset protection: invasive species widespread and abundant throughout its potential range.

Management methods to control the spread of weeds including: chemical, fire, physical or mechanical removal, grazing, biological control and hygiene.

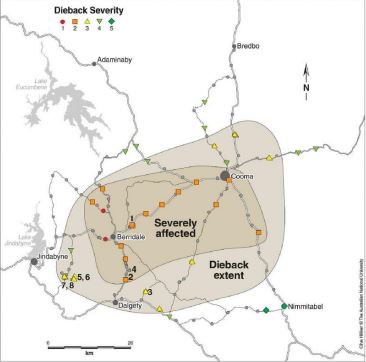

Great Mullein (Verbascum thapsus) (Figure 1) is an annual or biennial herb native to Europe and Asia but was introduced to Australia as a garden plant in 1845. This weed species is widespread throughout Australia except in the Northern Territory.

Figure 1. Photo of Great Mullein at the rosette stage.

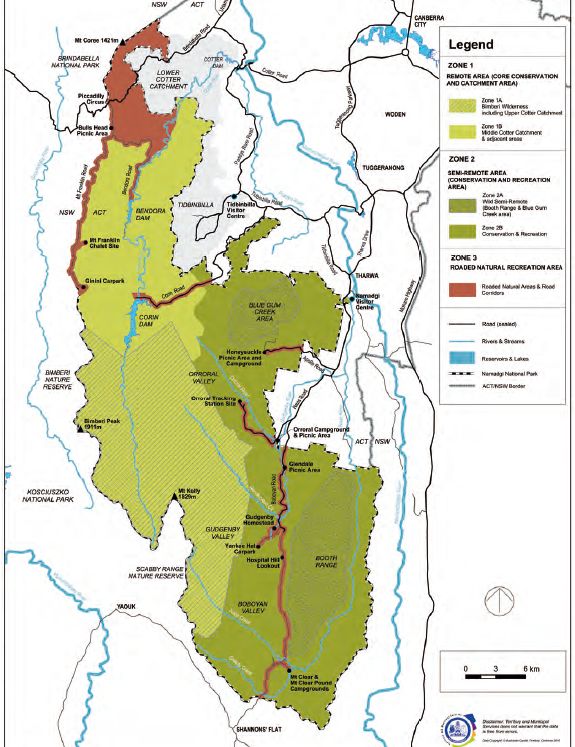

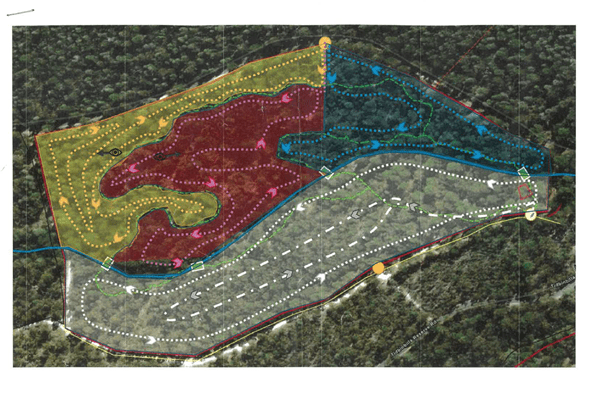

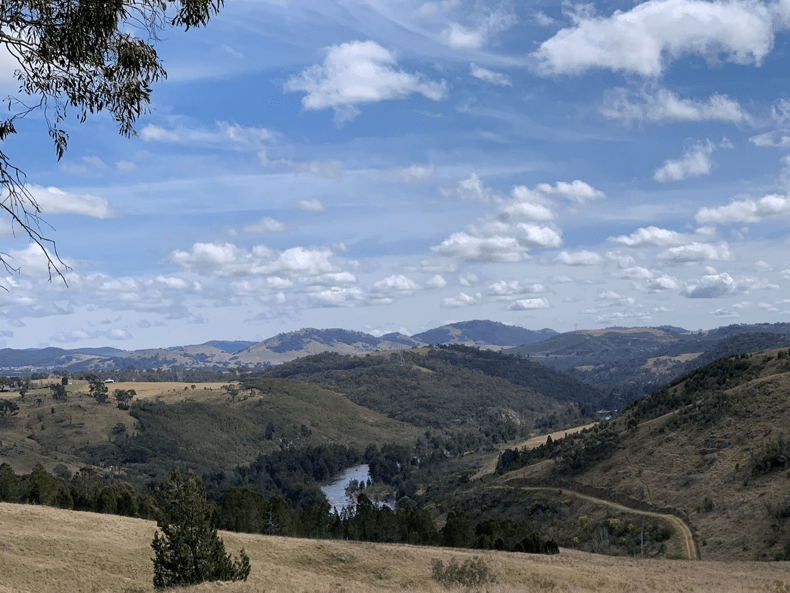

We used physical removal method to control the widespread of Great Mullein throughout the corridor of Ginniderry (Figure 2) with staff from Ginniderry Conservation Trust on 6th September. We removed the taproots of the Great Mullein by digging with shovels and turning the plants over to ensure the roots were completely disconnected from the soil (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Conservation Corridor in Ginninderry, Canberra.

Figure 3. Photo of weed control by manual removal.

Our team has removed a large number of Great Mulleins. However, it’s still not enough to control the spreading in Ginniderry area. It is important to continue monitoring and managing the weed species in order to reduce biodiversity loss.