U7121128 MJ Spencer-Stewart

The simplistic view that a niche remains vacant and with fixed borders following a species’ extinction is hopelessly naive. Nature abhors a vacuum, and any returning species has to fight to develop its own new niche. How can we predict what this niche will be?

Mark R. Stanley Price

The bird of the hour: The Bush Stone-Curlew

Once widespead, the Bush Stone-Curlew (Burhinus grallarius) went extinct in the Canberra region during the 1970’s. Threats from predation, mainly foxes, and habitat loss, due to clearing, have caused diminishing population numbers across the country causing classifications of endangered in New South Wales, threatened in Victoria, and rare in South Australia. Attempts conserve the species have led to curlew reintroductions, to mainly fox-free environments, at Phillip Island, Kangaroo Island, and Mt Rothwell Biodiversity Centre, among others.

What actually is reintroduction conservation?

The IUCN defines reintroduction as the release of an organism into an area that was once part of its range but from which it has been extirpated. With relatively little scientific literature until the 1990‘s, reintroduction and translocation of endangered species is becoming an increasingly successful conservation strategy. The IUCN Guidelines for Re-introductions places emphasis on the identification of reintroduction sites that are within the historic range of the species and the acknowledgement of the previous causes of decline with clear ways of addressing them.

I spy …

Volunteering for the lovely Sho Rapley’s PhD research on Bush Stone-Curlew reintroduction, I helped conduct a population survey at Mulligan’s Flat Woodland Sanctuary (MFWS). The unique 1253 ha of wildlife habitat enclosed by a 23km predator-proof fence is the secret to the curlews’ survival. First reintroduced to the predator-free sanctuary in 2014, with a total of 6 group releases to date. The reintroduction of the curlew to MFWS historically marked the return of the species to the ACT.

The survey we completed aimed to establish an estimate of the curlew population within the Sanctuary. Due to Covid lockdowns, population surveys weren’t able to be completed during previous years.

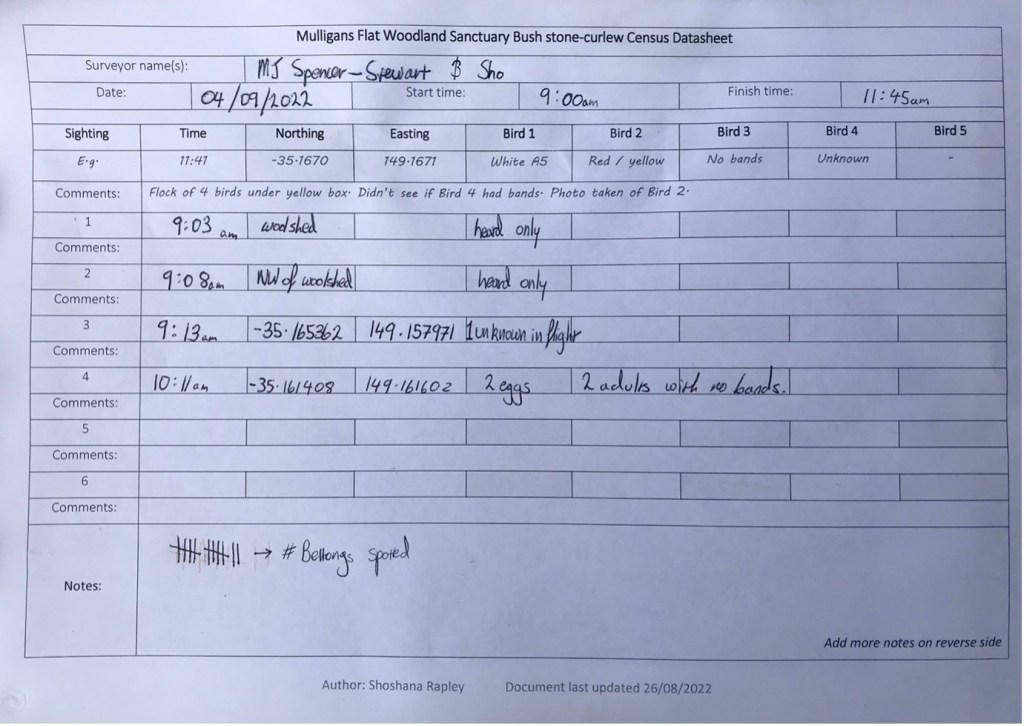

Splitting into groups and pairs, we were each assigned a polygon in the Sanctuary. Navigation during the survey was facilitated using Avenza Maps, an app that tracked our movement within the polygon (Image 1). Throughout the survey, any observed curlews and overheard curlew calls (distinctive) had to be noted on a census data sheet (Image 2). In ~2.5 hours we heard 2 calls, saw 1 adult curlew in flight, and spotted a mated pair along with their nest and eggs.

You call that a nest?!?

Sho and I were lucky to spot an un-banded nesting pair. Like the adult bird, Bush Stone-Curlew eggs perfectly blend with the landscape (Image 3).

Adaptive management

Reintroduction of any species a long a complex process that requires “identifying and assessing relative risks, specifying alternative outcomes in advance with indicators, and following it up [with] adaptively tweaked management.” The continued prosperity of the Bush Stone-Curlew at MFWS speaks to the success of continued adaptive management. The management of the curlews’ reintroduction meets all the IUCN aims: a site within the historic range of the species, addressing the fox threat with a predator-free space, addressing the threat of habitat loss with abundant suitable habitat type, and having ongoing management and monitoring, which in this case involves regular surveys, routine tagging of new individuals, the use of GPS backpacks, and more.

The preservation of endangered fauna and, by extension their ecosystem services, can be effectively achieved with reintroductions. But beware: success hangs on the quality of the monitoring.

I love the call of this bird and look forward to hearing it in Canberra. Phil