I took part in the annual ‘Echidna Sweep’ at Mulligans Flat Woodland Sanctuary, where a group of volunteers and scientists collaborated to monitor echidna numbers within the Sanctuary.

by Sophie Pinner (u7125901)

Our Prickly Protagonist

The beloved short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) is the only echidna species native to Australia, and one of four species in the world. Echidnas are “ecosystem engineers” which dig up and turn over soil, facilitating soil processes1.

Major threats to the echidna include invasive predators such as feral dogs, foxes and cats (which particularly prey on newborn “puggles”), as well as vehicle strike and habitat loss2. Although short-beaked echidnas in Australia are listed as ‘Least Concern’ there has been insufficient study on impacts and population size – with estimates ranging from 5 to 50 million!3

Mulligans Flat Woodland Sanctuary

Mulligans Flat Woodland Sanctuary is a 1251ha protected area in the north-east of Canberra, ACT, which conserves biodiversity and aims to restore the variety and abundance of wildlife that existed prior to European settlement.4

The sanctuary conserves Critically Endangered Yellow Box–Blakely’s Red Gum Grassy Woodland and works to rehabilitate the site back to its original composition. The Sanctuary provides habitat for a range of threatened and native species, including the echidna, which are protected by 22.8km of predator-proof fencing.4

The Sweep

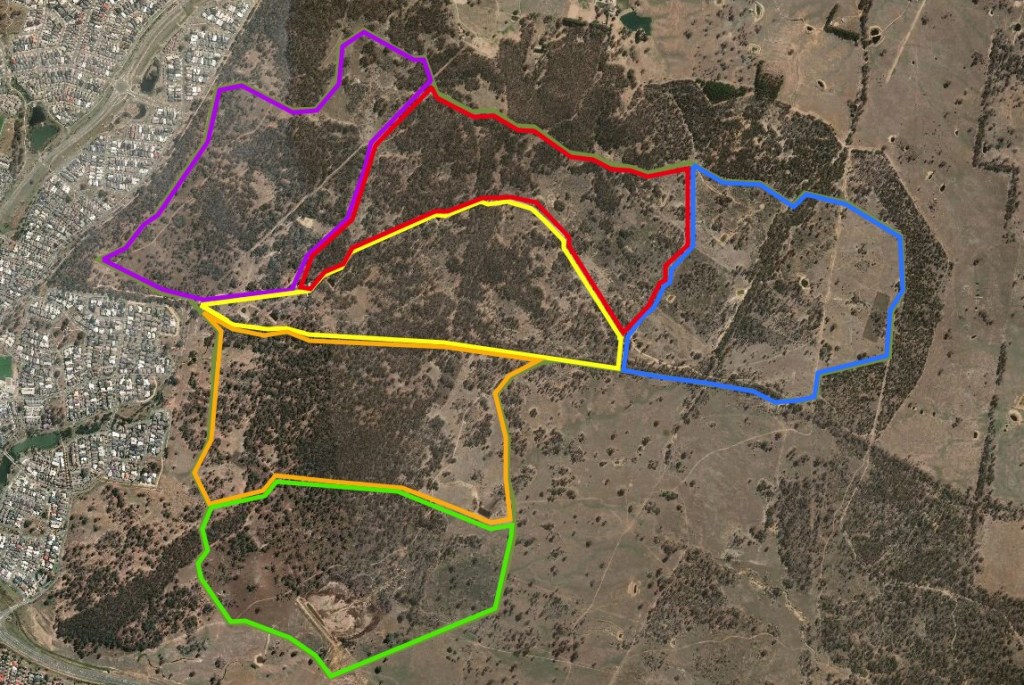

I volunteered in the annual ‘Echidna Sweep’ monitoring program at the Sanctuary, which has been occurring every year over two weekends in November since 2016. Every year, ~60 volunteers and team leaders sweep the sanctuary in groups of ~10-12 allocated to different ‘zones’.

When an echidna is spotted they are checked for markings, and if unmarked a team leader paints their quills with different colours of nail polish. This manicure gives the echidna a unique colour combination that can be used to identify it in the future. This Capture-Mark-Recapture method allows scientists to count ‘old’ and ‘new’ echidnas and use this result to estimate overall numbers.

Millie, the lead ecologist, explained that our estimates showed that the echidnas were in a positive state of population growth and the rate of puggle survival was much higher due to the lack of foxes.

Post-sweep reflections

The echidna sweep showed the ability of protected areas to allow native or threatened species to recover and thrive when external influences, like invasive predators, are removed and natural ecosystems are rehabilitated. This is crucial in the context of threatened critical-weight-range mammals in Australia, or the phenomenon of mammals in a ~35g-5.5kg range (e.g. puggles) being predated upon by introduced predators.5

Further, my experience showed me how passive adaptive monitoring in protected areas allows scientists to understand population health. This allows a direct response to threats (where necessary) through adaptive management.

Lastly, I understood the importance of citizen science, or active public involvement in science. I witnessed the sense of the community within the volunteers, and the engagement with hands-on learning. Everyone left the sweep at the end of the day feeling like they’d made a meaningful contribution, and that is truly invaluable.