An interview with Kirsty Yeates.

Paris Capell u6939944

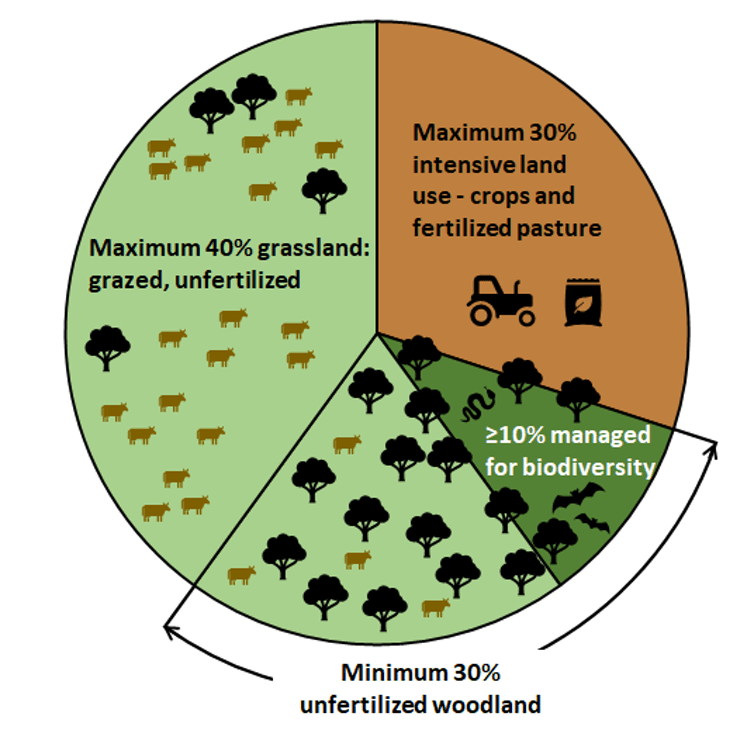

Biodiversity conservation is often managed through national parks and protected areas. However, as 58% of Australia’s landscape is managed for agricultural purpose through private landholders, how can we conserve biodiversity in the face of monocultural and intensive farming systems?

Regenerative agriculture: moving away from the farm system- natural system dichotomy

Regenerative agriculture (affectionately known as regen ag) is forecasted as the new paradigm shift for Australia’s conventionally farmed landscape. It aims to create a biodiverse and functioning ecosystem which also produces food and fiber. Kirsty Yeates is an agroecologist from ANU, working in a field of emerging importance when viewing biodiversity and agricultural land holders.

“For me agroecology is about understanding how the natural ecosystems work and then thinking how do we incorporate those natural processes and functions into a farming production system.”

Agroecology moves away from viewing conservation and farming as two separate entities, but rather integrating them to create better outcomes for both.

“I think one of the ways we’ve often thought about biodiversity conservation is what is already there, instead of reversing loss. Traditionally its either you can have a farm system or you can have a natural ecosystem. We can integrate both.”

Increased regen ag practices on private land not only has positive biodiversity outcomes, but it also increases the resilience and profitability of their system due to low inputs and increased productivity. For private landholders Kirsty believes:

“There are two elements to biodiversity- how do I have a more diverse system but also how can I integrate conservation outcomes into my system and there is some fantastic work from CSIRO and Sustainable farms who are looking at that innovation side.”

Biodiversity above and below the ground

While biodiversity is usually associated with above ground organisms, viewing farming systems through an agroecological lens highlights a key finding:

“We have to create more complex farm systems that can cope with and support a broader range of organisms so whether that’s birds or soil critters. For me I think the biggest gain are around soil biota, I think its important to recognize how much diversity is there.”

Kirsty uses a systems approach when viewing agricultural landscapes, and highlights that the biodiversity of soil microbes, fungi, earthworms and other organisms is intrinsically tied to nutrient and water cycling and is therefore the foundation for supporting more organisms above ground and increasing biodiversity.

“As farm systems increase their capacity for primary productivity over time, I think there is opportunity to increase the range of biodiversity.”

Katalpa Station: A Case Study

First hand, Kirsty is witnessing the change in mindset of private landholders . In the last few weeks she visted Katalpa Station in the Rangelands of NSW.

“I had the opportunity to go out with NSW DPI with a group of sol scientists and pasture ecologists out to these farms in the rangelands where they are doing a program called selecting for carbon. Its about understanding how their approaches to landscape management are changing the amount of carbon in the system and how that’s contributing other benefits like increased biodiversity.”

Kirsty summarises the relationship between regen ag and biodiversity:

“I think that regen ag potentially offers more opportunity to have a broader range of functions within a particular land unit which is being used for producing food and fiber, and I think we need to do more work in how we can make sure we get really positive biodiversity outcomes that align with conservation outcomes.”