Introduction, habitat and status

Image 1: A. parapulchella can grow up to 24 cm and feeds on the eggs and larvae of ants

Species profile

The Pink-Tailed Worm-Lizard (Aprasia parapulchella) is found in many sites in the ACT region. A. parapulchella are fossorial, and lives beneath stones and burrows that were previously formed by ant colonies, feeding specifically on ants, especially their larvae and eggs (Osborne and Jones, 1995). A. parapulchella are members of the family Pygopodidae (family of legless lizards), and can grow up to 24 cm. In the laboratory, it was observed that A. parapulchella is active during the day and not at night (Wong et al., 2011). They often live on the rocky areas of hillsides and upper slopes of river valleys, and are usually faithful to the same homicide over an extended period of time. A. parapulchella prefers sites that do not have tall shrubs and areas that are commonly covered by native grasses, especially kangaroo grass (Themeda triandra) (Osborne and Jones, 1995).

EPBC status: Vulnerable

The A. parapulchella is listed as a rare and vulnerable species under the EPBC Act, and are included in the Special Protection Status Species in the ACT. There is a high level of difficulty in conserving these species as A. parapulchella are habitat and dietary specialists, and have a low productive rate (Osborne and Jones, 1995). Because it is confined substantially in the ACT region, more funding is allocated by the government to conserve A. parapulchella in this area.

What makes it so vulnerable to decline?

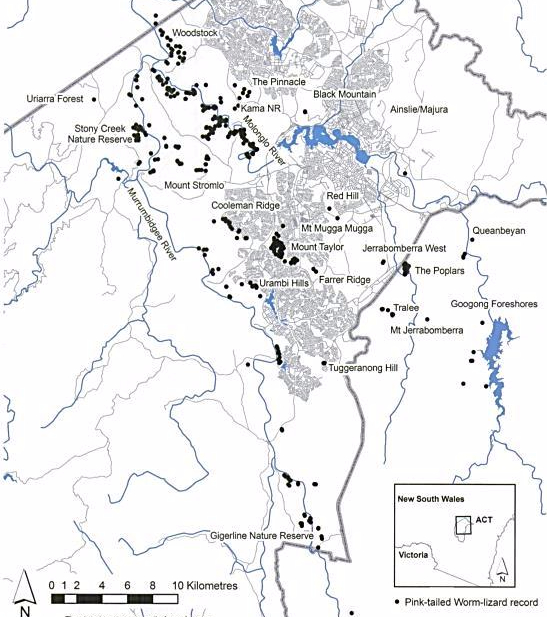

Livestock grazing, cultivation, inappropriate fire regimes and rock removal has contributed to the deteoriation of A. parapulchella rocky habitats. Livestock grazing and pasture cultivation removes the native grass cover of Kangaroo grass (Themeda australis), encouraging exotic weeds such as the African love grass (Eragrostis curvula) which are a hindrance as ants feed on native grasses. Other threats include the Coombs development that is occurring in the Molonglo valley, as there is a large population of A. parapulchella found along the Molonglo River (map 1).

Map 1: Distribution of A. parapulchella in the ACT region (Wong et al., 2011)

The reduction of patches resulting from the development of houses may significantly reduce the population size of A. parapulchella, leaving them with small patches that are more prone to patch scale stochastic events such as wild fires. Other threats to the species include climate change, and hence, building corridors for A. parapulchella are useful for them to adapt while moving.

Benefits to biodiversity

Sites that contain the A. parapulchella are found to support a richer reptile fauna, with up to 12 species such as skinks, which lives in the same habitat as A. parapulchella (Osborne and Jones, 1995). Thus, protecting the habitats and islands of the A. parapulchella will increase the number of reptile communities with a similar habitat type.

Field work

Image 2: Richard, an ecologist with the ACT Parks and Conservation Services (Reinfrank, 2015)

Richard (image 2) was our contact and an ecologist with the ACT Parks and Conservation Services. The survey site is located at Coppins Crossing in the Molonglo Valley, 7.5 km west. Richard shared with us that there are 4 species of Pygopodidae found in the Molonglo reserve, and is home to the highest number of A. parapulchella (map 1).

Image 3: Habitat islands of A.parapulchella

Molonglo reserve was previously fragmented by pine plantation due to the 2003 bush fires, and hence, Richard’s organisation has chosen to construct 11 islands made up of football sized rocks over a span of 4 areas for A. parapulchella to integrate into the new habitats. During the weeks prior to field work, Richard surveyed the other 9 islands and found them to be colonized. Our mission of the day was to identify A. parapulchella on the last 2 islands (image 3). This project started 4 years ago (year 2014).

Image 4: Multiple scales are evidence that A. parapulchella has made their homes in the bricks

Before field work began, Richard mentioned that there is a possibility that we might not catch a glimpse of these rare species, and told us to look for their scales that may be stuck to the rocks or bricks instead (image 4). A. parapulchella would shed their skins occasionally, and their skins will last for a few weeks up to a month.

Image 5: My excitement when an A. parapulchella is discovered

The optimal temperature is around 18 to 25 degrees Celsius, and A. parapulchella are rarely found when temperatures exceed 25 degrees Celsius, making it difficult to detect them in the summer. The temperature of the day of field work was 22 degrees Celsius. We started our search for A. parapulchella at 10:40 am, and at around 12 noon, we found our first A. parapulchella. There is often a huge amount of excitement and joy when we chanced upon an A. parapulchella (image 5), after all the hard work of turning over close to 1,000 rocks each.

Rocks or bricks?

Image 6: Red bricks have the closest thermal properties to rocks

Rocks appeared to be a harsh monitoring technique for A. parapulchella as rolling over the rocks could potentially destroy its burrows, and rocks makes it difficult to conduct a survey uniformly. Therefore, Richard and his team developed a low impact monitoring technique by using bricks (image 6) as habitats. Red bricks have the best thermal property aimed at keeping A. parapulchella warm at night and cool during the harsh summers. If successful, bricks could potentially be used as a national monitoring method for A. parapulchella.

Reflection

Are they using their habitat?

Image 7: A. parapulchella found under a rock

My personal take is that, yes, A. parapulchella are using the rocky habitats and bricks (image 7). These can be observed from the evidence of the scales they shed, and the 6 individual A. parapulchella that we were lucky enough to witness over the span of 2 Fridays. Furthermore, many of the rocks and bricks could be found with termites, larvae and multiple ant species building their nests. These will form a steady supply of food for A. parapulchella.

One fascinating takeaway was how A. parapulchella could co-habit with ants that it feeds on, and Richard speculates that this might be related to A. parapulchella leaving chemical signals that are desirable for the ant communities.

Other ways of managing A. parapulchella would be having a good fire regime plan in place. Placing rocks in the habitat is a great idea as it reduces the fire fuel load and increases ant occurrence, killing two birds in one stone. Furthermore, A. parapulchella were found to have colonized the restored habitat within one year of treatment (McDougall et al., 2016), proving its effectiveness. Thankfully, any development in Canberra is not allowed to spread over the lizard habitat, allowing these species to thrive for the years to come.

U5901018, Hui Tan

Dates of field work:

- 22 September 2017 10:30 am to 3:30 pm

- 6 October 2017 9:30 am to 1:30 pm

Total: 9 hours

Word count: 965 words, excluding in-text citation

References

McDougall, A, Milner, R, N, C, Driscoll, D, A, and Smith, A, L 2016, ‘Restoration rocks: integrating abiotic and biotic habitat restoration to conserve threatened species and reduce fire fuel load’, Biodiversity and conservation, vol. 25, no. 8, pp. 1529-1542, doi: 10.1007/s10531-016-1136-4.

NSW Government 2017, ‘Pink-tailed Legless Lizard – profile’, Office of Environment and Heritage. Available at: http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/threatenedspeciesapp/profile.aspx?id=10061

Osborne, W, S, Jones, S, R 1995, ‘Recovery Plan for the Pink-Tailed Worm Lizard (Aprasia parapuchella)’, ACT Parks and Conservation Service. Available at: https://www.environment.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/576810/Technical_Report_10.pdf

Reinfrank, A 2015, ‘Australia’s largest pink-tailed worm-lizard habitat restoration project underway to save threatened species’, ABC News. Available at: http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-05-09/pink-tailed-worm-lizard-habitat-restoration/6457362

Wong, D, Jones, S, Osborne, W, S, Brown, G, Robertson, P, Michael, D & Geoffrey, K 2011, ‘The life history and ecology of the Pink-tailed Worm-lizard Aprasia parapulchella Kluge – a review’, Australian Zoologist. 35. 927. 10.7882/AZ.2011.045.